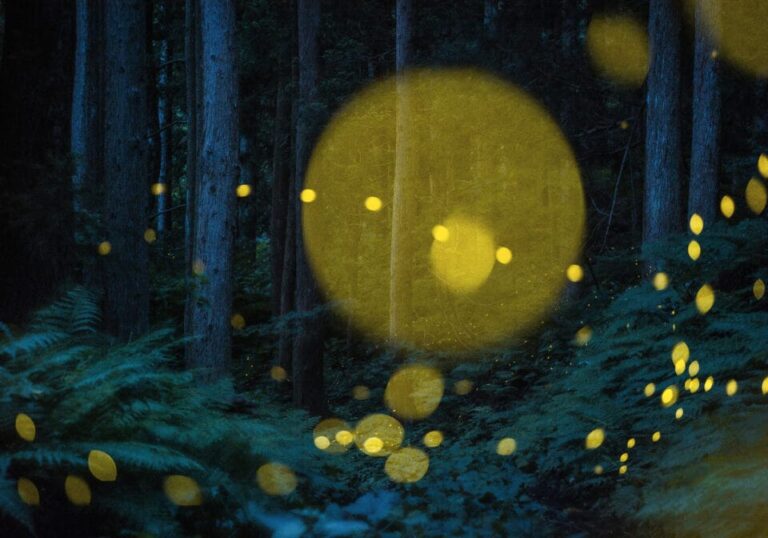

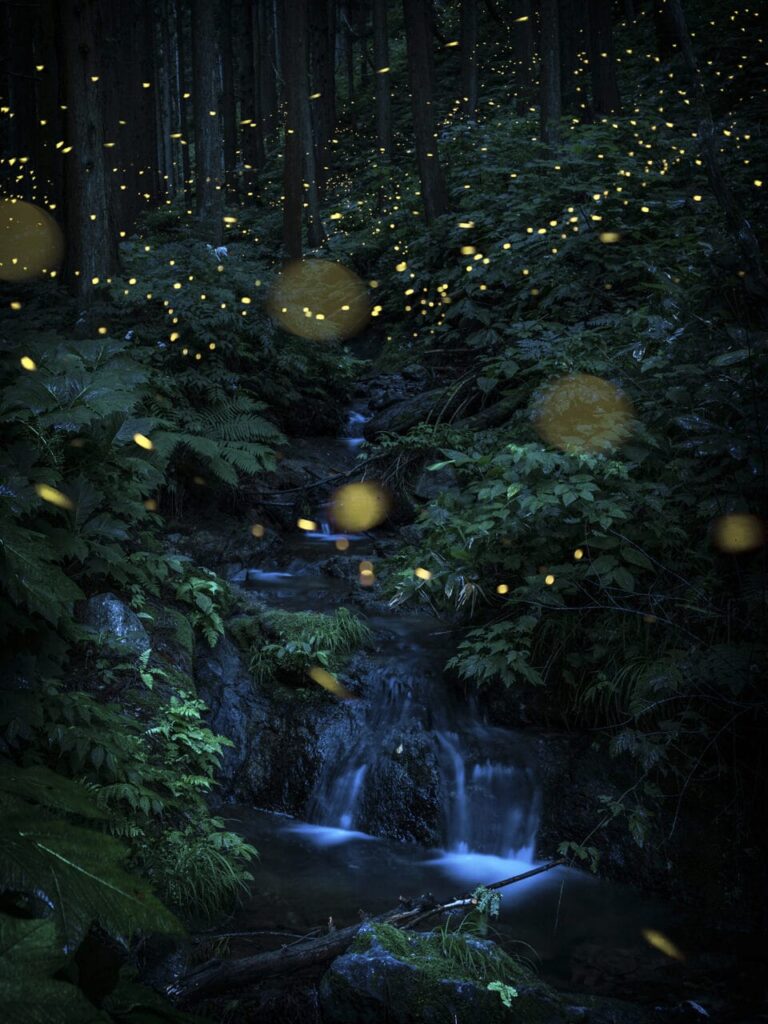

Summer Fairies

The Summer Fairies series is a lifelong exploration of the perceptual resonance between nature and humans through the ephemeral light of Japanese fireflies.

This series of works is printed on Washi paper, a handmade Japanese paper produced using a lengthy artisanal process, which gives these photographs a unique translucency.

Furthermore, the blue colour is not the result of digital manipulation but is the photographic transposition of what is known in Japanese culture as “The Blue Hour”, a very brief transition between day and night which, when photographed, produces this blue aura.

Through the fleeting light of Japanese fireflies in Yamagata’s summer forests, this series explores the perceptual resonance between nature and humans. It reveals the rhythms of life, the ethical dimension of sensing, and the profound wonder and fragility inherent in our environment. Each photograph is a co-creation with light and darkness, reflecting on time, unpredictability, and the deep continuity connecting past and present. This lifelong engagement with the forest and its luminous inhabitants informs every aspect of the work.

The works in the Summer Fairies series are printed Archvial pigment print on Handmade Japanese traditional ise-washi-paper in the following numbered editions:

A2 size

Image Size: 15x22inc (380mm x 560mm)

Paper Size: 17x24inc

Frame Size: 24x30inc

Edition 5 AP 2

Print 1 – 2 priced at 2000 USD

Print 3 – 4 priced at 2500 USD

Print 5 priced at 3000 USD

A1 size

Image Size: 22x33inc (560mm x 830mm)

Paper Size: 24.4x36inc (620mm x 920mm)

Frame Size: 28x40inc (728mm x 1030mm )

Edition 5 AP 2

Print 1 – 2 priced at 3500 USD

Print 3 – 4 priced at 4000 USD

Print 5 priced at 4500 USD

A0 size (in preparation)

Image Size: 31x45inc (780mm x 1150mm)

Paper Size: 35x47inc (900mm x 1200mm)

Frame Size: 40.3×56.4inc (1024mm x 1433mm ) or 37.6x52inc (956mm x 1320mm )

Edition 3 AP 1

Print 1 priced at 5000 USD

Print 2 priced at 6000 USD

Print 3 priced at 8000 USD

Artist’s Statement

In a forest so dark it evoked fear, I encountered countless lights.

They drifted through the trees like a sky of stars, transforming terror into beauty so profound that the vision has never left my mind.

Since that night, I have continued to ask—what image did that light carve into my brain?

That experience marked the beginning of the “Summer Fairies” series.

Since then, I have spent many summers observing the native Himebotaru fireflies in the forests of Yamagata,studying the intricate relationship between their glow and the environment that sustains it.

The sight of their lights dancing like a constellation within the forest is so dreamlike that it dissolves all fear of the night.

Their radiance, lasting barely ten days,feels like an eternal breath within the ancient cycle of life.

Before every photograph, I read the terrain, vegetation, humidity, wind, and subtle changes of light,trying to foresee the paths the fireflies might take.

Yet their movements can never be completely predicted.

Within that unpredictability lies the living rhythm—the breath—of existence itself.

Even before I photograph the darkness, I am already imagining it.

The digital camera I use is not merely a machine.

It converts light into electrical signals and perceives the world in a way akin to my own vision—an instrument with organic sensibility.

It receives the breath of the forest and the flicker of the fireflies as a perceptual circuit that reconnects nature, human, and technology.

This cycle of imagination and observation is, for me, an act of recovery—an intimate ritual to awaken the senses that modern humans have begun to lose. Through the intertwined experiences of fear and awe, it becomes an attempt to reconstruct perception itself.

The forests where the Himebotaru dwell are layered with time:

primary woods, regenerated forests shaped by logging and replanting, and fragments of the ancient wilderness divided by human development.

In these lands once inhabited by the Jōmon people, I listen and imagine how they might have perceived light.

I seek to approach the primordial sense of “listening” that the people of prehistory once possessed—a mode of hearing that allowed dialogue with the more-than-human world.

This is both a quest to reclaim the sensory perception of the ancients— who communed with the forest, water, and wind through their five senses— and a reconsideration of animism as an ethics of perception in our own time.

Through the camera, I paint together with the fireflies.

It is not an act of control, but of listening, of surrender, of co-creation.

Even now, as I continue to photograph, the fear of the forest’s darkness and the awe of the fireflies’ light have never vanished together.

Perhaps that coexistence is reverence itself — and the reason I continue this project.

Deforestation, climate change, and tourism are transforming the wild.

The light and silence of the nocturnal forest reveal, at once, both the fragility of life and the fleetingness of the environment we must protect.

The unpredictable traces of the fireflies speak not only of uncertainty, but also of an enduring hope for the future.

In an age of ceaseless conflict, the light of the Himebotaru quietly declares that life itself is a miracle worth preserving.

Each photograph is a dialogue between the forest, the fireflies, and myself—and at the same time, a prayer.

It is both a record of what continues to live,and a remembrance of what must never be forgotten.

This work seeks to expand photography beyond documentation—into a resonance of perception between nature and humankind.

.

What is Washi paper and how is it made

The Japanese paper washi is a traditional handcrafted paper from Japan, renowned for its lightness, strength, and refined beauty. The term washi comes from wa (Japanese) and shi (paper), and refers to a type of paper distinct from Western industrial paper.

Traditionally, washi is made by hand using natural plant fibers, mainly kōzo (paper mulberry), mitsumata, and gampi. The fibers are extracted from the inner bark of the plants, boiled and carefully cleaned, then beaten until a uniform pulp is obtained. A viscous substance called neri, derived from plants such as tororo-aoi, is added to help distribute the fibers evenly in water. The sheet is formed using the nagashi-zuki technique, in which the artisan rhythmically moves the screen through the water, layering the fibers evenly before natural drying.

One of the most fascinating characteristics of washi is its translucency. Thanks to the length of the fibers, their irregular yet harmonious arrangement, and the thinness of the sheet, light is able to pass through softly, creating a warm, diffused glow. This quality makes washi ideal for applications such as shōji (sliding doors and partitions), lanterns, artistic prints, and calligraphy.

In summary, washi paper is not merely a material support, but an expression of Japanese aesthetic sensibility, in which nature, craftsmanship, and light merge into a delicate and timeless balance.