Nobuyoshi Araki

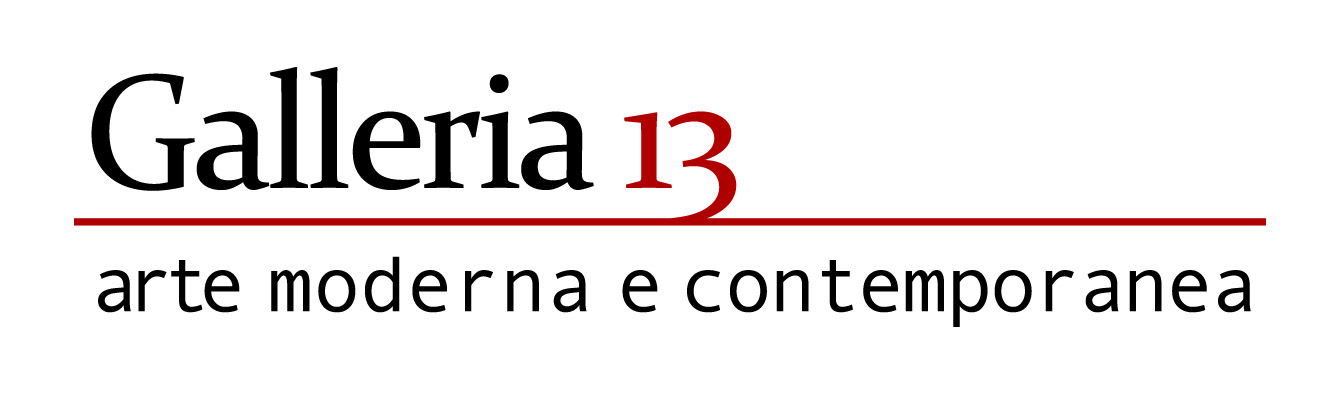

Nobuyoshi Araki (Tokyo, 1940), an engineer and filmmaker by training, is one of Japan’s most acclaimed photographers; he is known, in particular, for the erotic nature of his subjects, the situations he portrays and the prolific nature of his productions. Fascinated by women and the city of Tokyo, Araki documents everyday life with the idea of “showing everything” for what it is: he focuses his attention on the Japanese sex industry (from the ’80s he realizes reportages of Kabukich, the red light area of Shinjuku, a district of Tokyo – Tokyo Lucky Hole, (1983 – 1985) – continuously highlighting female sexuality; gagged, bound, provocative women. From 1963 to 1972 he worked at Dentsu Advertising Agency. In 1965 the first personal Shinjuku Station Building in Tokyo and marriage to Yoko Aoki in ’71, with whom he made the photographic diary Sentimental Journey during the honeymoon. Yoko died in 1990 of ovarian cancer: the photographs of her last days are collected in the book Winter journey.

Araki shoots continuously in black and white, in color, using simple equipment, illuminating flashes and Polaroids to obtain the maximum of spontaneity and immediacy. His research is aimed at investigating the boundary between life and death, between the apogee and the deterioration of beauty (as seen in the still life of flowers, beautiful, but already close to degradation). His themes are articulated in cycles almost obsessively interminable and autobiographical: Tokyo Nostalgy, Tokyo Diary, Tokyo Nude, Polamandara, Shousetsu Seoul. His is an art that divides, you can love or hate, but it is difficult to leave indifferent. When he looks at his metropolis he searches for a contact with all those lonelinesses he perceives in the crowd. Together with the photographic production he has dedicated himself to the cinematographic one, in particular through the project Arakicinema. In 2005 the director Travis Klose dedicated to him a documentary entitled Arakimentari.

Available works

Prints formats

25.4×30.5 cm – 35.6×43.2 cm – 50.8 x 61 cm – 60 x 90 cm – 76 x 101 cm – 100 x 150 cm

Flowers, 2007

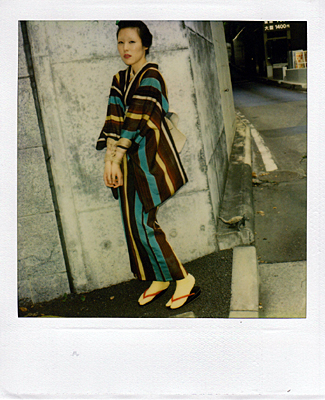

Shino

Shino is a japanese actress and one of the most favourite model of Araki

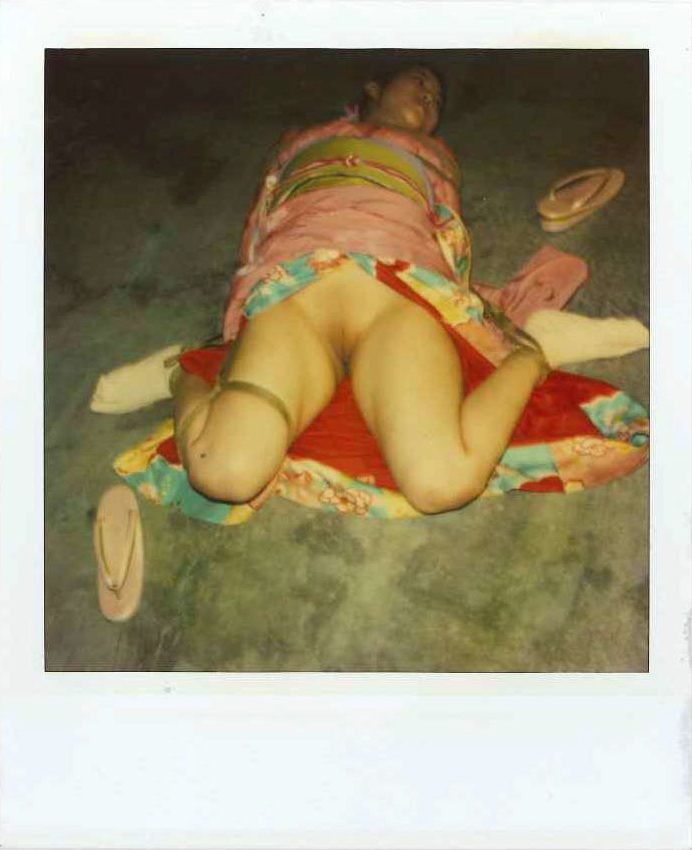

Woman and Watermelon, 1991

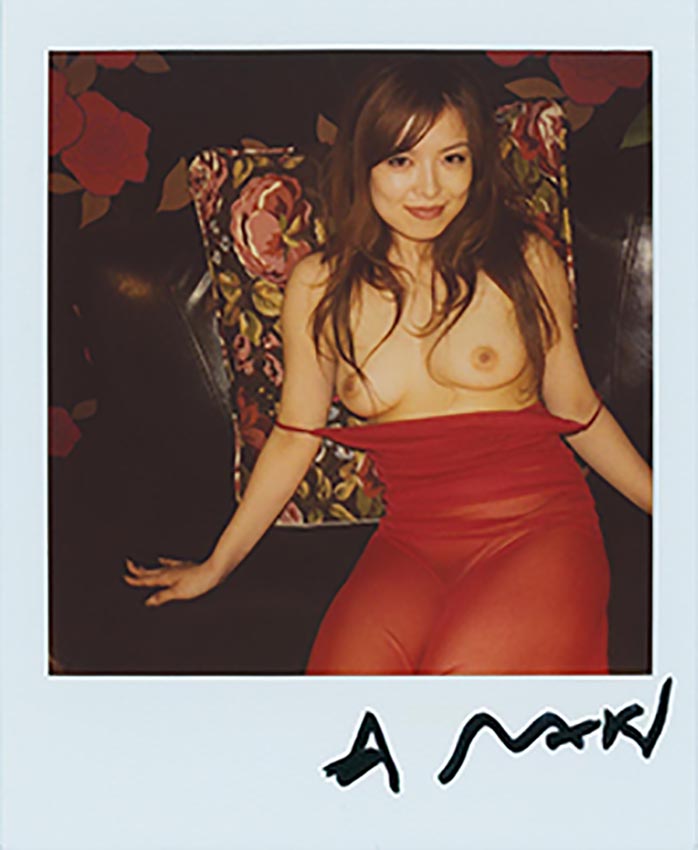

Komari

Komari is one of Araki’s muses and most famous model

Kinbaku

Maya Ayashi Portrait, 1980

Tokyo Commedy

Erotos, 1993

Sentimental Journay

Satchin, 1962/63

Nobuyoshi Araki

Satchin and his brother Mabo, 1963

Gelatin silver print

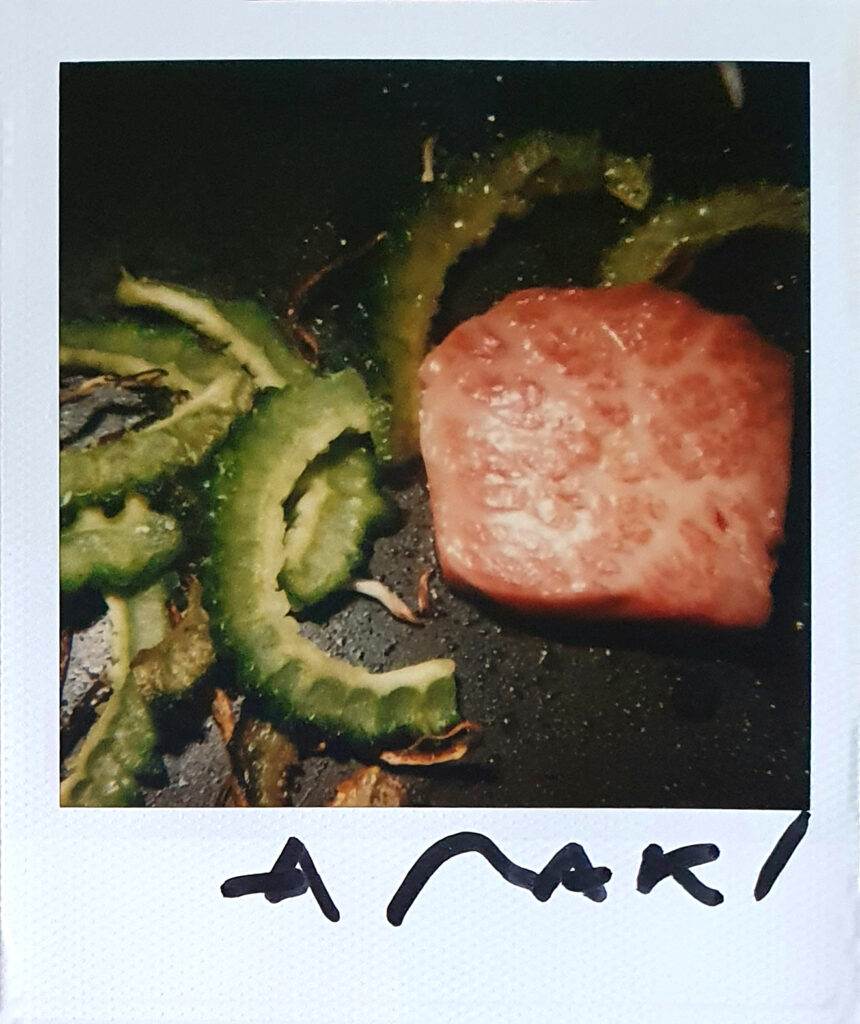

Polaroid in Gallery

10,8 x 8,8 cm

Signed on the front or back “Araki” in marker

Archive NA provenance, Tokyo

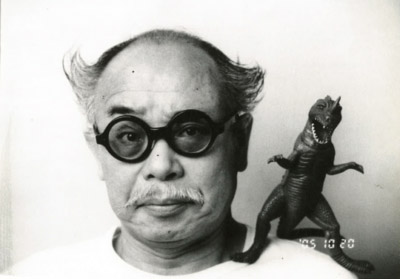

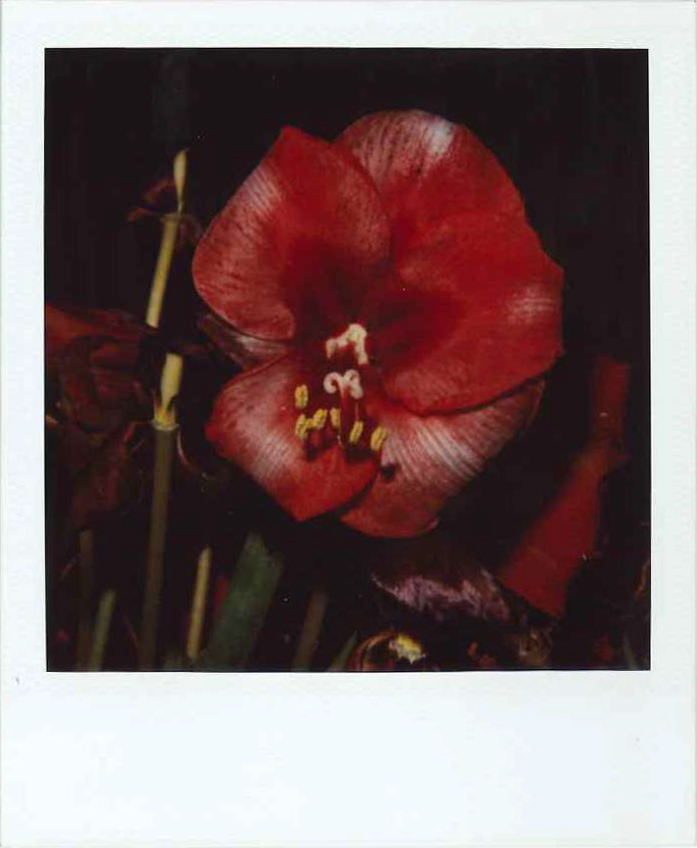

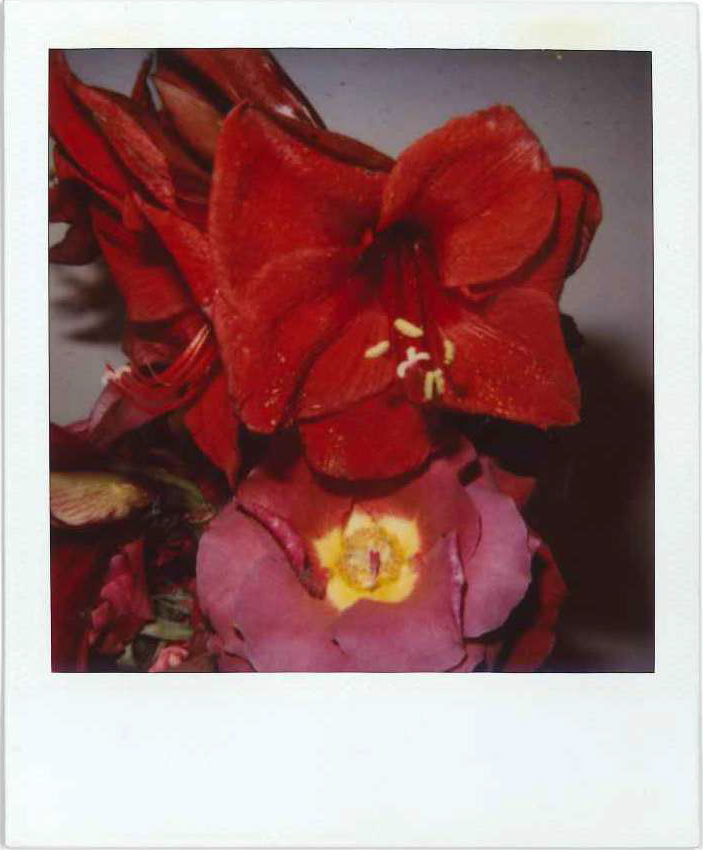

Flower Polaroid

01

Hand-signed on the front

02

signed on the front

03

signed on the back

04

signed on the front

05

signed on the front

06

signed on the front

Kinbaku Polaroid

01

Hand-signed behind, published

02

Hand-signed behind

03

Hand-signed behind

04

Hand-signed behind, published

06

Hand-signed behind, from shooting

Nude Polaroid

01

02

Hand-signed behind, published

03

Hand-signed behind, published

04

Sky Polaroid

01

02

03

04

05

Arakiri Polaroid

Arakiri polaroid is a very special polaroid that is the result of the artist’s ready-made. Araki loves to play with words, in this series of works he combines his name Araki with the word Harakiri, the Japanese ritual suicide, as in this ancient practice he cuts two polaroids in two and recomposes them into a new and unique work.

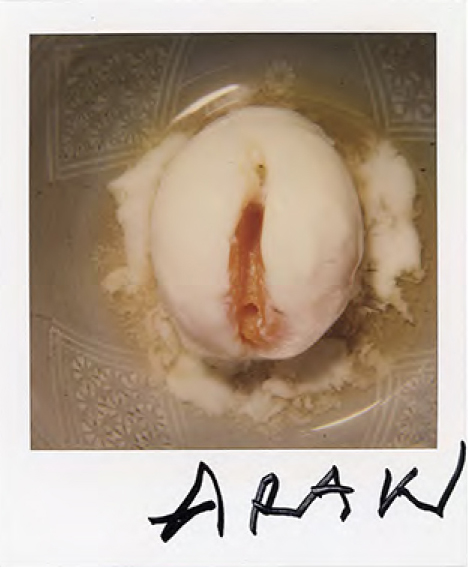

Food Polaroid

01

02

03

04

05

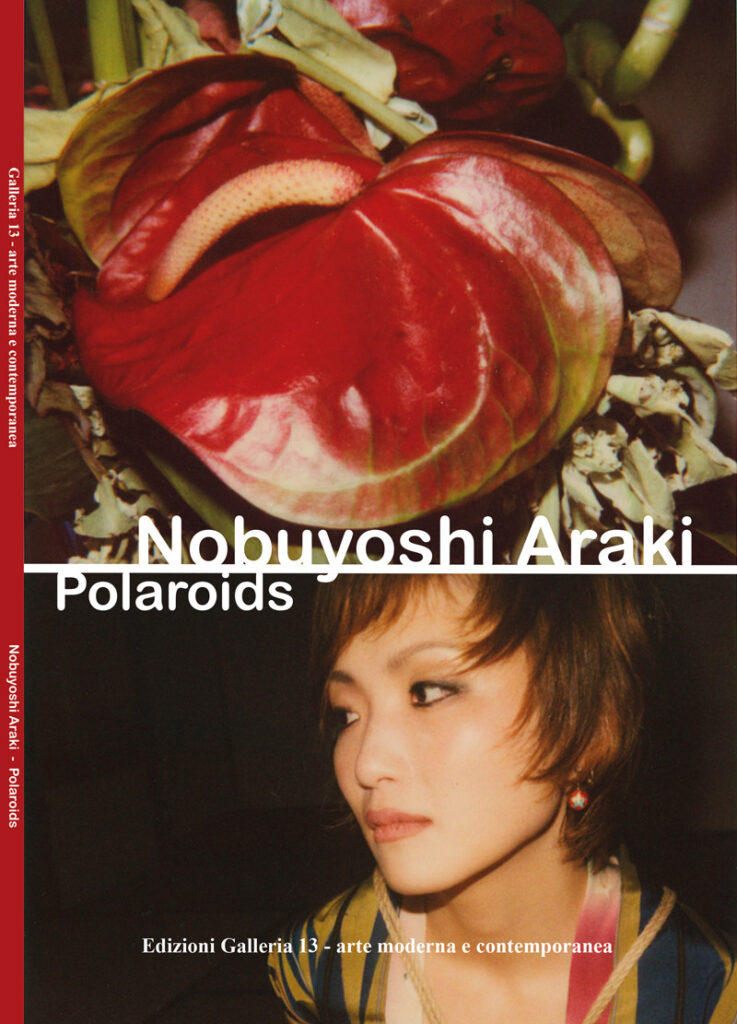

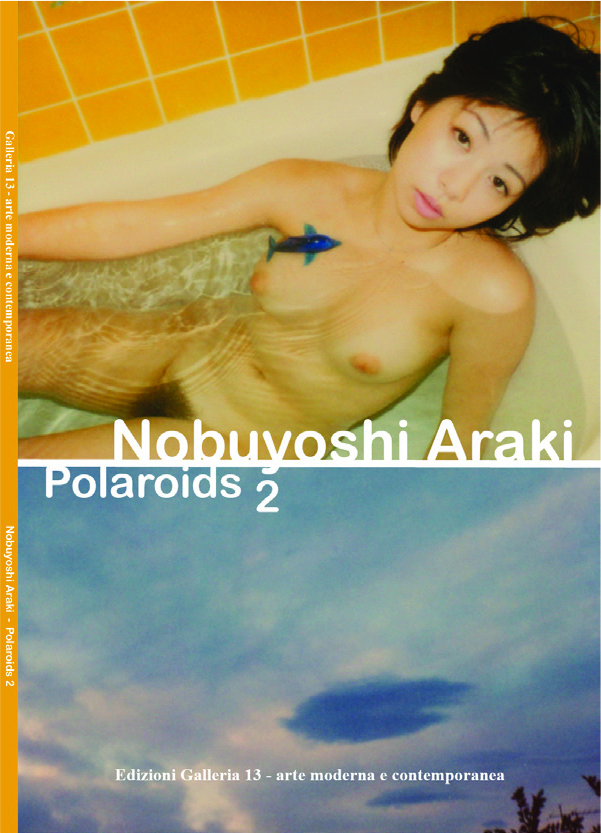

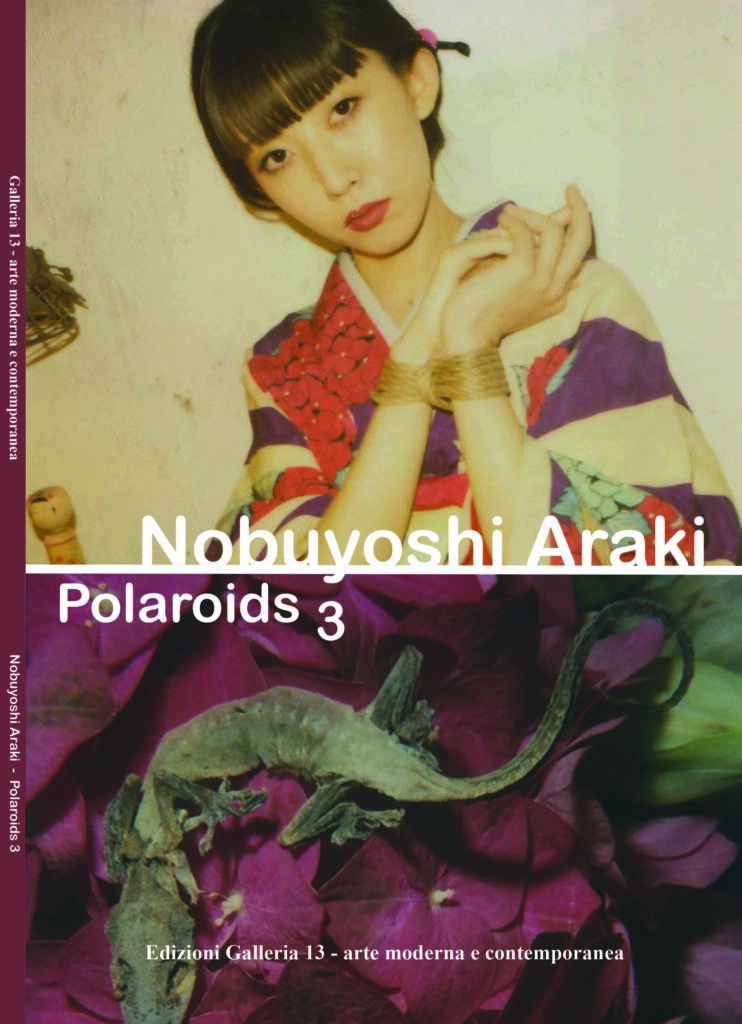

Araki's Catalogs

Gallery 13 has edited 3 volumes dedicated to Araki’s polaroids. Almost all of the polaroids for sale at Gallery 13 are published in these two volumes.

Catalogo Nobuyoshi Araki – Polaroid, SOLD OUT

Catalogo Nobuyoshi Araki – Polaroid 2

Catalogo Nobuyoshi Araki – Polaroid 3

FLOWER RONDEAU, 1997

Flowers have captured Araki’s imagination as symbols of Eros and Thanatos since his childhood. Growing up in the vicinity of Jyokanji Temple in central Tokyo, a place where the spirits of Yoshiwara’s courtesans were kept, Araki used to observe the cut flowers offered in cemeteries. For Araki, arranging decayed flowers is a form of rebirth, and photography eternally records the beauty of brevity.

Nobuyoshi Araki once observed that “to make static what is dynamic is a kind of death.” The camera itself, photography itself, invokes death. Also, when I photograph I think of death, which comes out in the print.” In Flower Rondeau, we immediately notice the contrast between life and death, brought to life by a half-closed flower displayed against a dark blue background. The flower’s veins emphasize its vitality, while the closed, withered petals demonstrate its fragility and the frailty of life itself.

Araki’s floral still lifes can be seen alongside the photographer’s kinbaku portraits as erotic and sexual visions. The open, transparent petals are captured in a state of revelation, comparable to the varying degrees of undress that his female models display. Flower Rondeau makes it clear that the flower is a reproductive organ by highlighting both the stamen and the carpel. As much as flowers die and decompose, they are also wombs where new life begins and the future materializes.

Who is Nobuyoshi Araki?

【Documentary】小米·大艺术家 荒木经惟(上):写真狂人的情与爱 Artists - Nobuyoshi Araki Part 1

【Documentary】小米·大艺术家 荒木经惟(下):写真狂人的生与死 Artists - Nobuyoshi Araki Part 2

Nobuyoshi Araki - Arakimentari

Nobuyoshi Araki (sottotitoli in italiano)

What is kinbaku?

Shibari or kinbaku, is a Japanese art that adopts hojōjutsu, or the act of binding a person. It can have several purposes, including relaxation of the body and mind, an artistic form of living sculpture, or a sexual practice.

The culture of shibari has very ancient roots. In traditional Japanese religious ceremonies, it has always been customary to include ropes and ligaments to symbolize the connection between the human and the divine.

The shibari was born in the fifteenth century, used by the police and samurai as a form of imprisonment, and as such remained until the eighteenth century. At that time the resources of metals were scarce, while hemp and jute ropes were abundant: so often prisoners were not locked up in a prison, but were simply immobilized with a rope. Japanese police still carry a bundle of hemp rope in their vans.

When it came to tying up a nobleman or a samurai there was always an artistic element, while certain shapes and designs made with the rope indicated to the spectators the social class of the accused (in Japan at that time the division into social classes was very rigid) and sometimes even the crime committed.

Shibari is Japanese-style rope bondage, a practice that consists of creating erotic bindings with ropes on a person’s body. Its origins are to be found in hojojutso, the martial art that involves the use of ropes to block and immobilize the opponent, then, around 1700, these techniques have taken on an erotic connotation when it began to use them in the artistic field in some scenes of kabuki theater or in the production of prints on the subject.

However, it will be only in the period between the two wars – and even more in the post-war period – that, especially thanks to the figure of Itoh Seiyu, shibari becomes a practice in its own right, clearly connoted in an erotic and sadomasochistic sense. The beginning of the 20th century saw Japan committed to becoming a modern nation, however the past was always present in the collective imagination and fascinated authors and artists such as the young Itoh Seiyu, considered the “father of kinbaku”.

Particular artist and much discussed, it was he who gave life to the art of bondage, through his paintings. To represent the tortures typical of the Edo period, he tied his models in various positions, immortalized them and from these photographs he drew inspiration for his paintings.

It will finally spread to the West after the Second World War after which shibari will be known first in the United States and from there throughout the world, also determining the development of different styles.

Kinbaku is instead a more recent term whose first written occurrence is in a Japanese magazine in 1952. It means “to bind tight”; “kin” means in fact “tight, firm, stable” and “baku” is another reading of the kanji that can also be read “shiba” (as in 縛り,shibari). According to some masters there is no difference between shibari and kinbaku; according to others instead “shibari” would simply be to make the Japanese style bindings, while “kinbaku” would refer to the binding but with in addition the deep emotional connection and all the relational aspects that are created between who binds and who is bound.

A complex erotic culture, where to stay tied to a rope in the void, a body against the other, skin to skin coordinating perfectly the movements to stay in balance. An art where the rituality of gestures, the brushing of hands and ropes on the skin of the partner, the complete abandonment constitute a sensual and complicit prelude to the love relationship. This, to those who love the genre, gives pleasure and excitement. But it certainly requires a lot of experience and attention, so as not to result in tragedy.

Tying is a very common practice in Japan, extremely rooted in the culture and in everyday life: from the art of wrapping gift packages, to the lacing of kimonos through the band called obi.

A special note deserves the practice of Mizuhiki, which consists of using small cords to decorate paper envelopes containing messages of greetings, thanks or condolences for friends and acquaintances.

The practice of Mizuhiki dates back to the Heian era (794-1185) when women of the court learned the art of creating decorative knots for gifts and letters.

The knots had a very precise meaning, a bit like what happened in Europe during the Middle Ages with the “language of flowers”, which then made the red rose to be associated to the idea of passionate love. During the Edo era (1611-1868) these laces were used for the typical hairstyles of the samurai. Even today Mizuhiki is used during weddings, to decorate the tables or other ornaments, dresses and hair of the bride. In addition, some artists use this technique to create real celebratory sculptures.

Also in the religious sphere, the history of Japan has numerous references to the use of ropes and knots. Shimenawa ropes are usually placed on the doors (the Torii) of Shinto temples and also on other sacred objects such as trees and rocks.

Even in Sumo, wrestlers wear ceremonial belts decorated with ropes that replicate the Shimenawa of the temples. The movements and rituals before the match serve to drive away evil spirits and invoke the arrival of beneficent gods.

Even Buddhism, although to a lesser extent than Shintoism, makes a symbolic use of knots.

The painter often used his second wife as a model. Famous is the episode in which the artist wanted to reproduce the scene of torture “Yoshitoshi” in “Oshu Adachigahara hitotsuya non zu (The house of Adachigara in Oshu), so he left his wife suspended upside down from the rafters, during pregnancy.