Vasco Ascolini

There is an Italian photographer who is the only one, along with Cartier-Bresson, about whom Sir E.H. Gombrich has written, whose photographs have been described as ‘exceptional’ by F. Zeri, who is a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres of the French Republic. Yet, the motto nemo propheta in patria fits him like a glove, because in Italy he remains very little known. His name is Vasco Ascolini and he was born in Reggio Emilia in 1937.

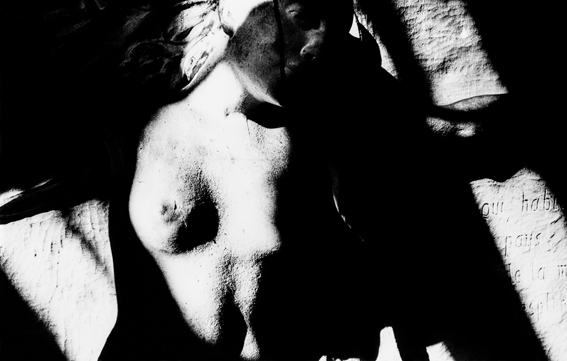

In the 1970s Ascolini attended lectures at the University of Parma, where American photography was rediscovered and people such as Mulas, Veronesi and Ghirri gravitated. When he began to collaborate permanently with the municipal theatre of his city, in parallel with his commission work, he embarked on a path of comparison between the language of photography and that of theatre, and moving on the basis of the theoretical reflections that Mulas himself had carried out on this theme, anticipating the Verifiche (Verifications), Ascolini sanctioned its irreducibility. However, proposing a critique of the complex concept of “true theatre photography” expressed by Mulas as the point of maximum approximation of the two languages, because it is still inadequate, Ascolini completely recreates the scenic event. The photographs of a performance by Lindsay Kemp in 1979 are defined by H. Gernsheim as “superbly expressionist”, and are the starting point of a completely personal and unmistakable style. Forcing the possibilities of the medium, he pushes the grain of the film, extremes the black and white tones, brings bodies closer to the lens and applies unexpected cuts to them, leaving much of the print to absolute black. The instinct of the shot and the rewriting in the darkroom influence each other, resulting in images of great formal balance played on asymmetries.

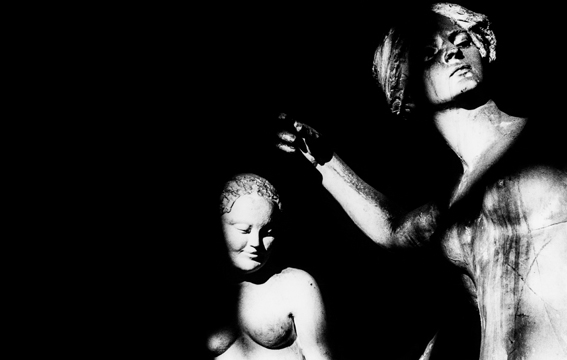

The subject of Ascolini’s photographs is always man, not here understood as a metaphorical expression of the human condition, but as an individual who, playing the role of actor on stage, is physically realised. It is no coincidence, therefore, that Ascolini devoted himself to dance and mimicry, the scenic arts in which speech is eliminated and everything is left to the body. In these images, through the occupation of the print up to the edges by the figures, man dominates the photographic space and becomes its measure, transfiguring himself. The blackness that opposes it defines it and also plays a perceptive psychological role, which is fundamental from the point of view of visual dynamics. On these figures, however, the erosion of the halftones and the merging, in the black, of the background with the shadows also generates an ambiguity between the living body and the statue that cites the poetics of Man Ray.

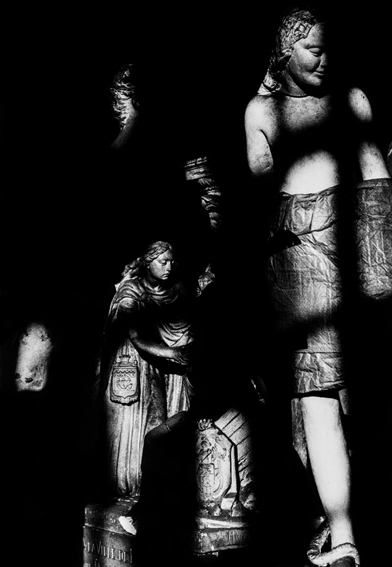

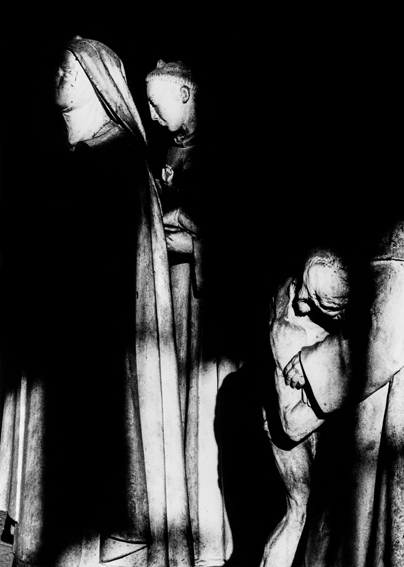

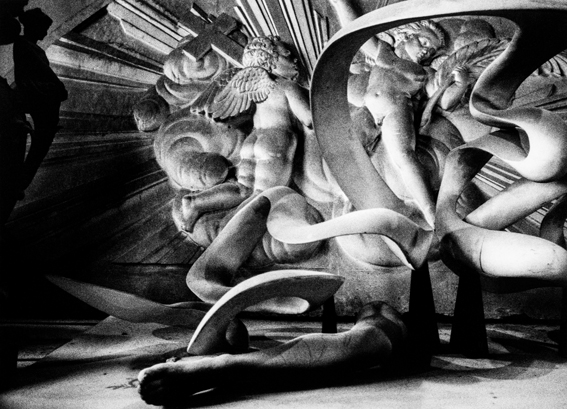

In the mid-1980s, Ascolini’s relationship with the theatre came to an end, and the photographer began to devote himself to an entirely different subject: architecture and historical statuary. The caesura, however, is only apparent. The stylistic features of the theatre are transposed onto stone and marble, halls and gardens, framed in an unusual way and sunk into blacks whose depth is freed from perspective flatness. In Ascolini’s interpretation of this, a very important influence intervenes, that of Giorgio de Chirico and Metaphysics. While remaining faithful to reality and the intrinsic characteristics with which the photographic medium relates to it, he succeeds in restoring in these images the atmospheres and sensations generated by the great painter’s paintings and which he himself theorised in his numerous writings. In Ascolini’s places, the human figure disappears, and, reversing the ambiguity of some of his theatre pictures, it is now the sculptures that appear human with subtle artifice, peeping out from behind a wall or showing their silhouette; everything is “calm and silent”, but this atmosphere coexists with a subtle restlessness. Even enigmatic combinations of objects, often depicted by de Chirico, are caught in reality by Ascolini in an alienating way and, as A. Scharf, ‘if we were to look at Ascolini’s subjects from life, they might look completely different from how they appear in his photographs’. If it is natural for the camera to isolate objects or recontextualise them, uncommon is the ability to lose their meaning and function in order to translate them into something else, something new, to recreate them.

Even the broad and absolute blacks, probably the most characteristic stylistic element of the photographer from Reggio Emilia, although formally distant from the clarity of Metaphysical Art, are here functional to the same logic: by hiding a part of the framed reality, often in a forced way, they increase the feeling of unease for what we are not allowed to see, for an absence that is not due – as already happened in many theatre photographs -, for something that seems to want to escape our perception. It is by leaving the door of reality ajar that Ascolini revives our imaginative capacity and prompts us to delve into the unconscious and memory.

Photographs

Unique piece

inkjet print on baryta paper infinity canson baryta photographique II

Kabuki Theatre

At the beginning of the 1980s, one of the most important Japanese theatre arts companies from Tokyo performed in the biggest theatres in Italy, including the Romolo Valli theatre of which Ascolini was the official photographer. Ascolini was therefore the only photographer allowed to photograph the secrets of the Japanese theatre arts, the fruit of centuries of tradition handed down from father to son. With his deep blacks, Vasco Ascolini captured the soul of these artists in an attempt to steal their secrets.

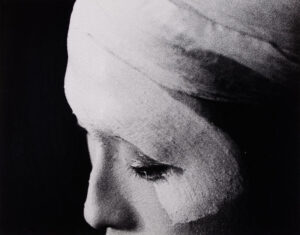

Onnagata

On’nagata male kabuki theatre character who puts on make-up as a woman in white

An onnagata (女方 ‘woman-shaped’) is a male actor who plays female roles in Japanese Kabuki theatre

Modern Kabuki theatre, consisting of all-male casts, was originally known as yarō kabuki (male kabuki) to distinguish it from its early forms. In the early 17th century, many Kabuki theatres had casts of only female actors (onna kabuki), some of whom also played male roles if necessary.

The practice of the onnagata was also widespread in the Wakashū kabuki (boy kabuki), a theatrical form born in 1612, in which a cast composed entirely of handsome young men played both male and female roles, often with erotic themes.

The onnagata and wakashū (or wakashū-gata) were the object of appreciation of both female and male audiences and often prostituted themselves. All-male casts became the norm after 1629, when women were banned from kabuki, due to heavy female prostitution and violent quarrels between customers who argued over the favours of actresses. This measure did not solve the problem, however, as young actors (wakashū) were also fervently sought after by customers.

“I asked permission to photograph Onnagata up close, and I got it: the Onnagata acting in Reggio was the fourth or fifth in his family to play that role, handed down from generation to generation.

I went to his dressing room; he arrived and immediately I noticed that there was nothing ambiguous about him, in fact he had a dark though freshly shaved beard. The makeup artist came in, he pulled down his kimono, and she began to apply white lead on his face and the back of his head; having finished her task, she went out. A short distance from him, who stood in front of a mirror, I set up the 85 mm lens, and while he put on his makeup and began the metamorphosis from man to woman, I photographed him repeatedly. In the type of framing I wanted to restore the ambiguity that we associate with the female figure, which always intrigues us and often eludes us.”

Japanese theatre arts

Alcune opere

01

Teatro danza

Gelatin silver print

02

Teatro danza

Gelatin silver print

03

Teatro danza

Gelatin silver print

04

Teatro danza

Gelatin silver print

Sculptures and museums

Architetture

Parigi, Louvre, Nike 2003

Sculture in movimento

Sculture in movimento

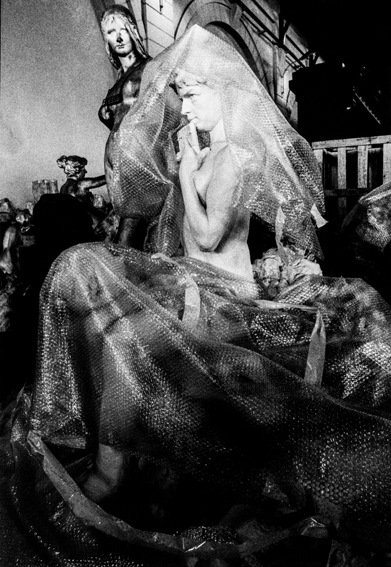

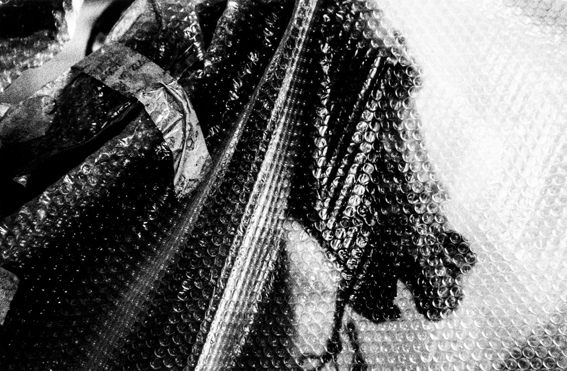

Sculpture Depot

DEPOSIT FIGURES is an unpublished project commissioned in 1996 by the French Ministry of Culture. Ascolini was asked to photograph the hundreds of sculptures removed from Parisian squares, streets and palaces and placed in this huge depot in Yvri, an old water-lifting workshop on the Seine, awaiting restoration. All the shots are taken on film, without the support of artificial lighting but only with natural light coming in through the skylights of the roof; he photographs at two different times of the year, spring and autumn.

The artist recounts: ‘When I was brought to the depot, the curator made me wait in front of a huge iron door that ran on rails. When it was opened I saw, less than a metre from me, a tide of sculptures that looked like a captive population awaiting liberation. Immediately my thoughts went back in time to when, as a child, I used to observe from the barn of my house the concentration camp of Fossoli and all the Jewish prisoners inside it. The memory is so vividly engraved in my mind that the rails of the gate seemed to me to be those of the train that brought the cattle cars straight into the camp and the sculptures seemed to me to be silent prisoners huddled together, wrapped in bubble wrap, and that is how I represented them.”

Biography:

Vasco Ascolini was born in Reggio Emilia on 10 May 1937, where he lives and works . He has been photographing since 1965. From 1973 to 1990 he was involved in theatre photography as the official photographer of the ‘Romolo Valli’ Municipal Theatre in Reggio Emilia.

His theatrical photographs can be found at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the MOMA in New York (Performing Arts Department), the Guggenheim Museum in New York and many other museums in the USA, Europe and other countries.

In 1985, a large anthological exhibition was organised in the exhibition rooms of the Lincoln Center in New York for his show photographs. In the area of “cultural heritage”, he was commissioned to photograph the great French museums such as the Louvre, the Rodin, the Carnavalet, etc.

While continuing to print and exhibit these images, from the end of the 1970s, he began to deal with photography related to architectural and museum heritage, always preserving his ‘black figure’ that had already distinguished him in his theatrical shootings. In the 1980s, even in this new genre, he was given institutional assignments, first and foremost that of photographing the city of Aosta. Each assignment was carried out while maintaining an absolutely personal vision and without conditioning.

His meeting with Michèle Moutashar was very important: she gave him an assignment to photograph Arles and exhibited it at the Rencontres in 1991, giving him international visibility in this new genre as well. He received the Grand Medal of the City of Arles.

In 2000, he exhibited at the major exhibition “D’APRES L’ANTIQUE” at the Musèe du Louvre, which showed “photography” as such in a group show for the first time. Also in 2000, he was appointed Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture.

In 2007, the Province of Reggio Emilia dedicated a retrospective exhibition to him in his city, Reggio Emilia, curated and with texts by Sandro Parmiggiani and Fred Licht. A catalogue was printed for SKIRA editions on the occasion.

01

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

02

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

03

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

04

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

05

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

06

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

07

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

08

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

09

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

10

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

11

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

12

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

13

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

14

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

15

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

16

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

17

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

18

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

19

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

20

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

21

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

22

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

23

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

24

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

25

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

26

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

27

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

28

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

29

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

30

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

31

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

32

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

33

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

34

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

35

Deposito sculture – Parigi

Gelatin silver print

Photographs on request available in the VA Archive

Interview with Vasco Ascolini

Without Judo and Zen I would never have become an artist

“Black and white instinctively prefer them to colour… from pure white to intense black, they are my ‘palette’.

What is contemporary art to you?

To me, Contemporary Art is everything that is created by artists as they pass through this territory of creativity. It is determined by the sharing of groups of brilliant artists who have ideas and ideals that can be shared with each other. Then of course there is the great mass of other lesser creatives who follow in their footsteps. I give an example by writing about the brilliant French artist Yves Klein in the early years of the last century (April 1922-June 1962). His appearance pointed to new ways forward: he was the forerunner of Body Art, which is still attended by artistic personalities such as the great Gina Pane. In each of his periods Klein was disruptive. Nouveau Réalisme, Conceptual Art, thus arriving at a new Contemporary Art. He “married” Zen Philosophy, learned in the years 1954/55 in the Kodokan Martial Art Temple in Tokyo, Japan. He followed the Zen dictates of Shintoism and Buddhism. He writes that it was this philosophical period that made him an artist. His contemporary art, and that of his sodalists such as Arman, Spoerri etc., set the school. Photography is part of it.

What is beauty?

Beauty is that emotion that each of us feels before something or someone that illuminates us with a unique Light, never seen before.

How was Master Vasco Ascolini born?

It was born badly, since the World War was coming. It was 1937. From an early age I was prey to illnesses later multiplied in the famine of the war. I missed three years of elementary school, two of them displaced to the countryside by cousins in Carpi, Modena. A few yards from the house was the Fossoli concentration and sorting camp for the extermination camps in Poland for Jews. I saw what I was not supposed to from a small window looking into that place of death. I remember it always following me. So I went through elementary and middle school three years older than my classmates. In middle school – playing soccer where I was very good – a pleurisy stopped me and left a year and a half later; I was sent from the Sanatorium in Reggio Emilia, to the one in Castelnovo Monti. At the magistral school I was discouraged, I was older than everybody by three years…I flunked, I never understood math and geometry…. Then there was military service where I was an instructor NCO to new recruits. There I decided that I had to give myself an education and I started reading, systematically, as if I were still in school. In fact more so.

In your opinion has something been lost because of today's frenzy? It used to be that artists met, confronted each other in cultural venues, today thanks to or because of the media there can be more individualism and less confrontation?

Absolutely. The ability to make groups has been lost, I Vociani in Florence at the Café delle Giubbe Rosse, at the Café Rosati in Rome, at the Café de la Rotonde and at le Dõme in Paris, where the Surrealists measured each other, had fights, but then drank together and talked about Art. Today the groups that exist are only amateurs in all disciplines. Those who emerge keep a few students close by, one or two; I now have one, a 50-year-old girl, Anna Maria Ferraboschi. The first one, Cesare Di Liborio, has become better than me.

Can you tell us briefly about theater photography?

It was my transition to professionalism. Back at City Hall, the Reggio Emilia theater needed a photographer who would not only photograph the performances, but also the very spirit of the moments of culture, for example, the arrival of the sets at the carriage gate, the way the objects were left in a disorder that André Breton and the Surrealists would have loved. I called this work of mine “The Fiction Begun.”

How come you chose the medium of photography as your form of expression? How come black and white?

Because I couldn’t paint or even draw or sculpt, so I thought about Creative Photography full-time. I accepted and it was for me the most beautiful and important period of my life. I entered, in the 20 years of work (1971/1991), into symbiosis with that Art that was emerging next to the other now established ones. Photography was already attended by my older brother from whom I borrowed his camera. I left for the Po, on the left bank of Reggio Emilia looking at the source, I applied to my photographing a rhetorical figure ” pars pro toto,” which then followed me all my life. A part for the whole. I selected, photographically, the dry riverbed and made material abstractions from it. I immediately won a contest. Black and white is because, instinctively, I prefer it to color…from pure white to intense black, it is my “palette.”

Which encounters with prominent figures touched you the most and which encounters do you carry with you the most?

The meeting with Ernst H. Gombrich et Jascques Le Goff. I saw them leave in my depths, first Gombrich then Le Goff. I still pray for them, even though I know they were not believers of any religion. I carry more with me the encounter with Gombrich, because I frequented him the most. He came to Italy four times and never failed to call me so that we could meet. I also listened to his last lecture, on Pico della Mirandola, a lectio magistralis in front of the top specialists on that character. Everyone stood and applauded him, a real standing ovation…. Gombrich wrote only two photographic texts, one for Cartier Brésson and one for Vasco Ascolini.

It is fascinating your relationship with Japan and the martial arts of which you are a black belt, do you feel like telling us about it?

In Reggio Emilia, from a small group of do-it-yourself Judo amateurs, a real gymnasium came into being founded by a German who was passing through our town and had learned this type of Art in Japan. Westerners made it into a sport, but philosophical Judo like Yves Klein’s is Dance, is Theater. Judo stands on the Kata where you learn the sense of levitation, the ability to overcome the force of gravity, to make yourself empty in front of an attack and create emptiness behind your enemy, the leap into the void … from very high up to the ground … malleability and yielding. I am a black belt 2nd dan, instructor of the Italian National Federation.

The magazine is called Quid Mgazine because it wants to investigate that spark that makes something unique; where do you glimpse the quid in your work or life?

The “Quid” in my life was all that thwarted me, poor health and little opportunity to study. This situation made my Quid a source of energy and intolerance of those who wanted to put a “wall” between me and success. Although in another field of culture I behaved like the poet Emily Dickinson. Closure yes, but not defeat.

Light, then the visible, appearance and appearance. What connotation do they have in your life. Appearance and appearance are either positive or negative elements. Today we live in a world that is more and more about appearance, the pursuit of light as the limelight what do you think about that?

For me, Appearance is positive, unlike appearance which is negative, and today, in fact, everyone is looking for Appearance and Ephemerality. I certainly don’t.

Available books

Vasco Ascolini - Fotografia

A memoir in which Ascolini recounts his encounters with great figures in art history, artists, critics, curators and major international collectors throughout his career

10 euro – signed

Vasco Ascolini - Low Tone

Raccolta di fotografie teatrali

20 euro – signed